Animal: Black and white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegate), 16-year-old (adult), male.

Organ/cavity: Caudal body cavities and inguinal canal.

History: Previous history of echinococcosis affecting ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) and a white-handed gibbon (Hylobates lar) at the UK zoological collection, with the last case reported in 2017. In 2023, this adult male black and white ruffed lemur exhibited clinical signs of inappetence and general malaise, with marked abdominal extension. He was euthanised following the identification of innumerable free-floating intra-abdominal cysts on ultrasonography, and subsequent clinical deterioration.

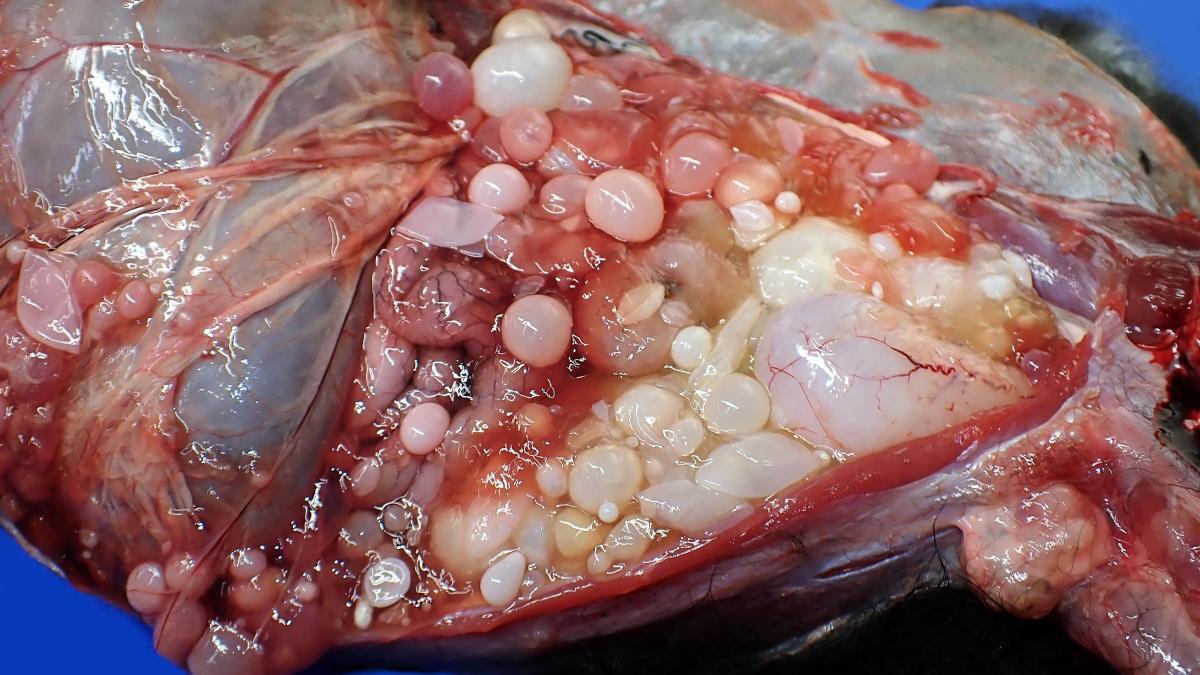

Necropsy findings: The abdominal cavity was markedly distended and contained hundreds of both intact and collapsed, spherical, thin-walled, clear to opaque, cream to dark pink cestode hydatid cysts (ranging in diameter from approximately 2 to 50 mm) containing clear colourless watery fluid and innumerable <1mm diameter, fine, cream-coloured hydatid sand particles. Some cysts were loosely attached widely to the omental and mesenteric connective tissues, and occasionally to the gastric serosal surface, the hepatic capsule, and the splenic capsule; however, most were observed free-floating within the peritoneal cavity. The scrotum was also enlarged, and upon incision through the skin, vaginal tunics were packed with multiple free-floating and adherent larval cestode cysts, ranging from approximately 1 to 6 mm in diameter, which compressed the testes. Cysts extended along the inguinal canal, and adherent clumps of cysts were present in the pelvic canal dorsal to the bladder, extending around the colon/rectum and incorporating prostate, seminal vesicles, and proximal penile urethra. Examination of the cyst contents under a dissecting microscope yields occasional spherical/granular structures suggestive of protoscolices; however, morphology was poorly defined in many cysts (degeneration vs autolysis).

Molecular identification of hydatid cysts: Genomic DNA was extracted from one hydatid cyst. PCR and DNA sequencing for three genes (16S, 28S, cox1) was conducted:

• 16S: PCR and sequencing was successful and identified the sample as Echinococcus ortleppi.

• 28S: PCR and sequencing was successful, however there are no published data on GenBank that matched the results (highest percentage match was 90% Dictyterina cholodkowskii), these data could not be used to confirm the Echinococcus ortleppi results obtained with the 16S gene.

• Cox1: PCR was not successful.

The resultant DNA sequences are available upon professional request.

Morphological diagnosis: Caudal body cavities and inguinal canal - Severe, chronic, diffuse, peritoneal, pelvic, and inguinal hydatidosis/echinococcosis.

Aetiology: Echinococcus ortleppi

Name of the disease: Hydatid disease.

Comment: Molecular speciation confirmed Echinococcus ortleppi as the infective Echinococcus species in this black and white ruffed lemur. In general, lemurs appear to be a relatively common aberrant intermediate host for tapeworms. Over recent years, cestode infections in lemurs have included Echinococcus multilocularis in France,15 Canada,6 and Japan5 (rodent-fox/canid lifecycle), Echinococcus granulosus in Israel11 and the UK (dog-sheep lifecycle),3 Echinococcus equinus (dog-horse lifecycle), 3 and Echinococcus ortleppi3 (dog-cattle lifecycle) seen in various locations across the UK, plus Taenia crassiceps in Poland,10 Serbia,13 Austria,16 Spain,8 and the USA,14 Taenia martis in Italy2 and Germany,9 and Hymenolepis nana in USA1 and China.7 Each Echinococcus species is associated with a variety of intermediate and definitive hosts, of which wild foxes and domestic dogs are most important in the UK as they can shed tapeworm eggs in faeces, which may be relocated into enclosures by fomites (e.g., via footwear), posing infection risks for lemurs if food is contaminated. Another route is direct enclosure/food contamination (i.e., faecal shedding by wild foxes) if enclosure boundaries are poorly maintained. There was no evidence of shedding of tapeworms in the faeces of infected primates, and so further infection of conspecifics is unlikely. Such cases are, therefore, sporadic in collections and based on the random ingestion of faecal-contaminated food. In this case, the dog/fox-cattle lifecycle is most relevant and so tapeworm screening/treatment of Bovidae near this enclosure may be considered, plus reinforcement of enclosure boundaries to reduce the likelihood of dog/fox contamination.

Contributors: Dr Andrew F. Rich BVSc DiplECVP AFHEA MRCVS (International Zoo Veterinary Group (IZVG) Pathology, West Yorkshire, UK; contact email: a.rich@izvg.co.uk), Dr Andrea Waeschenbach BSc PhD (Science, Natural History Museum, London, UK), and Claire Griffin (Sequencing Facility, Science Innovation Platforms, Natural History Museum, UK)

References:

1. Crouch EE, Hollinger C, Zec S, et al. Fatal Hymenolepis nana cestodiasis in a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta). Vet Pathol. 2022;59(1):169-72.

2. De Liberato C, Berrilli F, Meoli R, et al. Fatal infection with Taenia martis metacestodes in a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) living in an Italian zoological garden. Parasitol Int. 2014;63(5):695-7.

3. Denk D, Boufana B, Masters NJ, et al. Fatal echinococcosis in three lemurs in the United Kingdom—a case series. Vet Parasitol. 2016;218:10-4.

4. Dyer NW, Greve JH. Severe Cysticercus longicollis cysticercosis in a black lemur (Eulemur macaco macaco). J Vet Diag Invest. 1998;10(4):362-4.

5. Kondo H, Wada Y, Bando G, et al. Alveolar hydatidosis in a gorilla and a ring-tailed lemur in Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 1996;58(5):447-9.

6. Kotwa JD, Isaksson M, Jardine CM, et al. Echinococcus multilocularis infection, southern Ontario, Canada. Emerg infect dis. 2019;25(2):265.

7. Li B, Zhao B, Yang GY, et al. Mebendazole in the treatment of Hymenolepis nana infections in the captive ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta), China. Parasitol res. 2012;111:935-7.

8. Luzón M, De La Fuente-López C, Martínez-Nevado E, et al. Taenia crassiceps cysticercosis in a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2010;41(2):327-30.

9. Peters M, Mormann S, Gies N, et al. Taenia martis in a white-headed lemur (Eulemur albifrons) from a zoological park in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Vet Parasitol: Regional Studies and Reports. 2023:100913.

10. Samorek-Pieróg M, Karamon J, Brzana A, et al. Molecular confirmation of Taenia crassiceps cysticercosis in a captive ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) in Poland. Pathogens. 2022;11(8):835.

11. Shahar R, Horowitz IH, Aizenberg I. Disseminated hydatidosis in a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta): A case report. J Zoo Wildl Med. 1995:119-22.

12. Schulze C, Thielebein J, Maksimov P. Concurrent alveolar hydatid disease in four captive ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) from a zoological garden in Germany. J Comp Path. 2020;174:173.

13. Simin, S., Vračar, V., Kozoderović, G. et al. Subcutaneous Taenia crassiceps Cysticercosis in a Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur catta) in a Serbian Zoo. Acta Parasit. 2023;68:468–472.

14. Young LA, Morris PJ, Keener L, et al. Subcutaneous Taenia crassiceps cysticercosis in a red ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata rubra). In: Annual conference AAZV 2000 (pp. 251-252). American Association of Zoo Veterinarians; 1998.

15. Umhang G, Lahoreau J, Nicolier A, et al. Echinococcus multilocularis infection of a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) and a nutria (Myocastor coypus) in a French zoo. Parasitol Int. 2013 Dec 1;62(6):561-3.

16. Wiesner M, Glawischnig W, Lutzmann I, et al. Autochthonous Taenia crassiceps infection in a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) in the Salzburg Zoo. Wiener Tierärztliche Monatsschrift. 2019;106(5/6):109-15.